Research

My research focuses on the relationship between genetic variation and the path of evolution. Natural selection requires genetic variation to act upon, but the action of selection removes that variation from the population. My work explores the interplay between these forces, taking advantage of genomic data from many individuals and multiple populations in order to create an unbiased picture of genetic variation across a species.

Much of my work has involved studying natural populations of organisms that have been long been used as laboratory models: the ‘fruit’ fly Drosophila melanogaster, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, and the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Most laboratory studies in these organisms are performed using the progeny of a small number of strains, and often only a single genetic background. While this approach has led to many great advances in biology, understanding the variation present in the species allows us to put laboratory findings in context. At the same time, the variation present in natural populations can be very different from the mutations that are commonly induced in the lab or may cause those laboratory mutations to behave quite differently. This makes natural varaints a rich source of new genetic information that we can use to make discoveries that may not be possible using only the standard laboratory strains.

Patterns of variation in S. cerevisiae

The brewers yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was the first eukaryote to have its genome completely sequenced. It has long been a favorite model organism for the studies in genetics and cell biology, and over time the yeast research community has built fantastic genomic and functional resources that make it an ideal system for the study of evolutionary genetics, both in the lab and in natural populations.

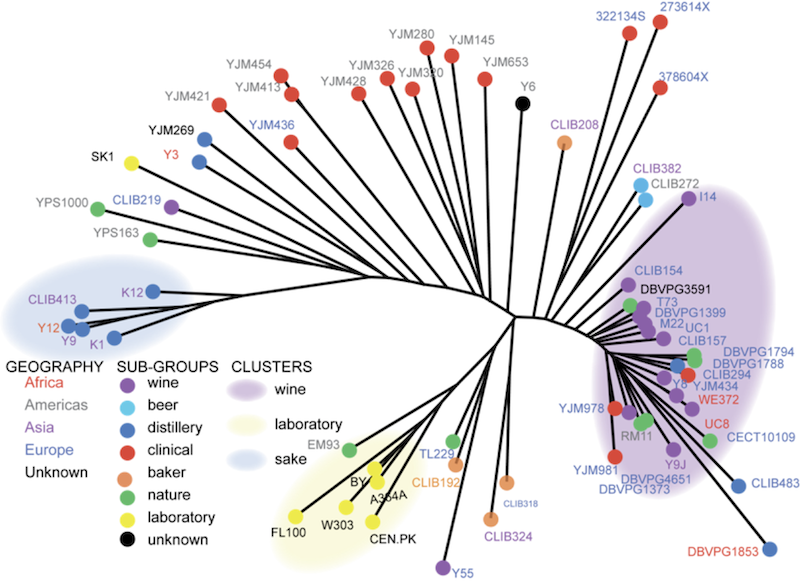

Working with Joseph Schacherer, I examined genomic variation in strains of yeast collected from around the world in different environments, both natural and industrial. These data clearly demonstrated strong population structure in S. cerevisiae, most likely largely driven by strong selection of domestication for winemaking, sake production, and laboratory work. In addition to these major groups, there were also many strains that appeared to be the results of more recent hybridization between groups, including many of the strains which were isolated from human infections (S. cerevisiae is not normally pathogenic, but it can infect immunocompromised individuals). Again, the best way to find out more is to read the original publication in Nature: Comprehensive polymorphism survey elucidates population structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (free version at PMC).

While the overall diversity of yeast is low compared to many other species, there is still quite a bit of diversity to explore among these strains, and in new strains collected from the wild. One goal of my current research is to conduct focused sampling of yeast diversity at particular sites to deepen our understanding of the patterns of local adaptation in yeast. Can we detect signatures of natural selection over short time scales or in specific locales? How do these small-scale patterns of evolution relate to the global patterns of diversity that we have observed? How the patterns of evolution in wild yeasts relate the patterns that have been observed in experimental evolution of the same species?

Global selective sweeps in C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans is a globally distributed species of nematode that lives in decaying plant material and soil. It has been used as a model for developmental biology and genetics for over 50 years, with work on the species resulting in three Nobel prizes. Almost all of this work was done using a single strain, but there has long been interest in the natural variation and population genetics of the species.

Despite having having large population sizes, which tends to increase diversity, C. elegans was known to have fairly low genetic diversity (a level similar to humans), and it was widely suspected that this low diversity was largely the result of the fact that C. elegans is a selfing hermaphrodite with rare males, a life history that tends to result in greater power for purifying selection. Even mutations with very small negative effects will tend to be eliminated fairly quickly by natural selection, taking with them neutral variation, in a process called background selection.

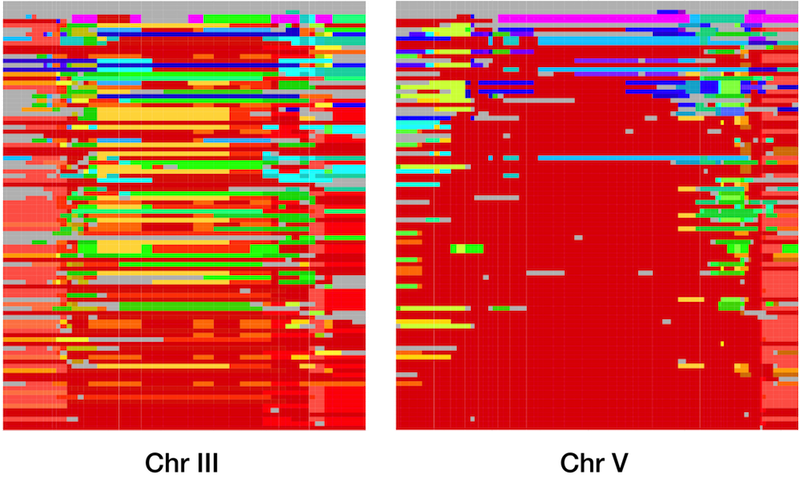

Together with Erik Andersen and Justin Gerke, I undertook a large-scale study of the global and genomic diversity of C. elegans, using high-throughput sequencing of restriction site associated DNA (RADseq) to examine over 200 wild isolates. We began by confirming the general patterns of diversity that had previously been observed using smaller data sets, but our data allowed us to see patterns that had never been appreciated before. Not only was overall diversity low, but on three of the six C. elegans chromosomes, large regions were completely identical across strains collected from all over the globe. These long blocks of identity are compelling evidence for positive selection, and our simulations indicated that the global spread of these haplotypes occurred only in the past few hundred years.

This strong selection and rapid spread indicates that some allele or combination of alleles in each of these haplotypes was strongly favored in the recent past. Unfortunately, the size of the haplotypes and their high frequency in the population mean that the current data do not help us much in identifying the genes which were under selection. Complete genomic sequences for the strains will help, as will data from more strains, as the global collection of C. elegans continues to expand. These data, especially from strains that do not contain the common haplotypes, will also allow me to explore whether the recent sweeps are unusual within the history of C. elegans, potentially driven by human interactions, or if such sweeps have much more common through the history of the species than we had anticipated.

If you are interested in exploring this in more detail, you could do worse than to read the paper we published in Nature Genetics: Chromosome-scale selective sweeps shape Caenorhabditis elegans genomic diversity (free version at PMC). There was also a nice News and Views article by Patrick Philips published alongside the original article (not free).